Notes from Java Concurrency in Practice

I read the Java Concurrency in Practice by legendary Brian Goetz about four years ago

and collected a lot of notes in my physical notebook.

The purpose of this post is to refresh my memory by going through the notes and to publish them for everyone else’s benefit.

The book was written in 2006 - a very long time ago, but according to Brian Goetz

all of it is still relevant, missing only the coverage of some new features.

However, the Project Loom might be a rather strong reason for a new version of the book.

Anyway, here are my notes from the book.

PART I - Fundamentals

Thread Safety

Threads are everywhere - era of multicore processors!

Even if your app is single-threaded you might use a framework that calls your classes from multiple threads, so they need to be thread-safe.

Object’s state is its data, stored in state variables such as instance or static fields.

Shared variable is the one that can be accessed by multiple threads.

- Don’t share the state variable across threads

- Make the state variable immutable

- Use synchronization whenever accessing state variable

A class is thread-safe when it continues to behave correctly when accessed from multiple threads.

Thread-safe encapsulate any needed synchronization, so that clients need not provide their own.

We collectively refer to check-then-act and read-modify-write sequences as compound operations.

Compound operations must execute atomically in order to remain thread-safe.

Where practical, use existing thread-safe objects - AtomicLong, AtomicReference<T>, ConcurrentHashMap, etc.

A synchronized block has two parts: reference to an object that will serve as the lock, and a block of code to be guarded by that.

synchronized (lock) {

// modify shared state

}A synchronized method is a shorthand for a synchronization block that spans an entire method, and whose lock is the object on which the method is being invoked.

synchronized void modifySharedState() {

// modify shared state

} These built-in locks (any java object) are called intrinsic locks or monitor locks.

Intrinsic locks are reentrant - if a thread tries to acquire a lock it already holds, it will succeed.

All accesses to a mutable state must be preformed with the same lock held - in this case, we say a variable is guarded by that lock.

Avoid holding locks during lengthy computations or operations at risk of not completing quickly (network, I/O operations, etc.)

Sharing Objects

Locking is not just about mutual exclusions; it is also about memory visibility.

To ensure threads can see the most up-to-date values of shared mutable variables the reading and writing threads must synchronize on common lock.

Volatile keyword ensures that values updated are read/written to the main memory, not to local CPU caches.

This is not from the book

Volatile variables can guarantee only visibility; locking can guarantee both visibility and atomicity.

Volatile is not good for compound operations. The most common use is completion, interruption or status flag.

Thread confinement - if data accessed only from single thread no synchronization needed.

Stack confinement - an object can be accessed through local variables, which are intrinsically confined to executing thread.

Conceptually, you can think of ThreadLocal<T> as a Map<Thread, T> that stores thread-specific values.

In reality, it’s not implemented that way - values are stored in the Thread object itself (thread dies, data die).

An object is immutable if:

- Its state cannot be modified after construction

- All its fields are final

- it is properly constructed - “this ref” doesn’t escape

Good practice to make fields final unless needed otherwise.

To publish an object safely:

- Initialize an object ref from static initializer

- Store a ref into volatile variable or AtomicReference

- Store a ref into a final field of a properly constructed object

- Store a ref into a field that is guarded by a lock

Composing Objects

Designing thread-safe class

- Identify the variables that form object’s state

- Identify the invariants that constrain the state variables

- Establish policy for concurrent access to the object’s state

Instance confinement - encapsulating object within another object - so you can ensure synchronized paths (delegated methods) to the encapsulated object.

Private lock is better that object’s intrinsic lock - client code cannot acquire it.

When implementing client-side locking make sure you are using the correct lock (look at documentation what lock is used).

@NotThreadSafe

public class ListHelper<E> {

public List<E> list = Collections.synchronizedList(new ArrayList<E>());

...

public synchronized boolean putIfAbsent(E x) {

boolean absent = !list.contains(x);

if (absent)

list.add(x);

return absent;

}

}Why wouldn’t this work? After all, putIfAbsent is synchronized, right? The problem is that it synchronizes on the wrong lock. Whatever lock the List uses to guard its state, it sure isn’t the lock on the ListHelper. ListHelper provides only the illusion of synchronization; the various list operations, while all synchronized, use different locks, which means that putIfAbsent is not atomic relative to other operations on the List. So there is no guarantee that another thread won’t modify the list while putIfAbsent is executing.

Here’s the thread-safe version of it:

@ThreadSafe

public class ListHelper<E> {

public List<E> list = Collections.synchronizedList(new ArrayList<E>());

...

public boolean putIfAbsent(E x) {

synchronized (list) {

boolean absent = !list.contains(x);

if (absent)

list.add(x);

return absent;

}

}

}Document a class’s thread safety guarantees for its clients; document its synchronization policies for its maintainers.

Document design decision at its design time - later the details maybe blur - write down before you forget!

Building Blocks

Delegating thread-safety to existing thread-safe classes is one of the most effective strategies (e.g. ConcurrentHashMap, etc.)

Use ConcurrentHashMap, CopyOnWriteArrayList, CopyOnWriteArraySet and others instead of their “synchronized” peers in Collections.synchronized*

size() and isEmpty() in concurrent collections semantically weakened, so they provide an approximation rather than real exact number. But in concurrent frameworks they are far less useful.

copy-on-write collections are reasonable to use only when iteration is far more common that modification.

Blocking queues are a powerful resource management tool for building reliable applications; they make your programs more robust to overload by throttling activities that threaten to produce more work than can be handled.

How to handle InterruptedException:

- Propagate the InterruptedException use whenever possible

- Restore the interrupt - catch the exception and restore its interrupted status by calling interrupt on the current thread

Synchronizer - any object that coordinates the control flow of threads e.g. semaphores, barriers, latches.

Latch - acts as a gate; until the latch reaches the terminal state the gate is closed and no thread can pass.

Once the latch reaches the terminal state, it cannot change state again, so it remains open forever.

Barrier - similar to latches - blocks group of threads until some event. The key difference is that with barrier,

all the threads must come together at the barrier point in order to proceed. Latch waits for event, barrier waits for other threads.

A barrier implements the protocol some families use to rendezvous during a day at the mall: “Everyone meet at McDonald’s at 6:00; once you get there,

stay there until everyone shows up, and then we’ll figure out what we’re doing next.”

Semaphore - is used to control the number of activities that can access certain resource or perform given action at the same time.

A semaphore manages set of virtual permits; threads can “acquire” permits and “release” permits. If no permit is available, “acquire” blocks until one is (or until interrupted).

Using a semaphore you can turn any collection into bounded blocking collection - a semaphore initialized to the desired maximum size of collection.

The add operation acquires a permit (blocked if no permit available), a successful remove releases a permit, enabling further addition.

FutureTask - is used by the Executor framework to represent asynchronous task, and can also be used to represent any potentially lengthy computation that can be started before the results are needed. Future.get() returns the result if completed, otherwise blocks until the task transitions from waiting/running to completed state.

public class Preloader {

private final FutureTask<ProductInfo> future = new FutureTask<>(Service::loadProductInfo); // new Callable

private final Thread thread = new Thread(future);

public void start() {

thread.start();

}

public ProductInfo get() throws DataLoadException, InterruptedException {

try {

return future.get();

} catch (ExecutionException e) {

throw new DataLoadException(e);

}

}

}The less mutable state the easier to ensure thread-safety.

Make fields final, unless they need to be mutable.

Hold locks for the duration of compound actions.

Guard all variables in an invariant with the same lock.

Document your synchronization policy.

PART II - Structuring Concurrent Applications

Task Execution

Thread creation and tear down are not free.

Active threads consume system resources, especially memory. When there are more runnable threads than processors,

threads sit idle. Idle threads tie up a lot of memory putting pressure on garbage collector.

Whenever you see new Thread(runnable).start() and you think you might need a more flexible solution in future, seriously consider Executor.

The real performance pay-off comes when there are number of independent, homogeneous tasks that can run concurrently.

Cancellation and Shutdown

Java doesn’t provide mechanism to safely force a thread to stop. Instead, it provides interruption - one thread asks another to stop.

Each thread has a boolean interrupted status; interrupted a thread sets its interrupted status to true.

The poorly named static method Thread.interrupted() clears the interrupted status of current threads and returns its previous value. It’s the only way to clear the interrupted status. The actually check the status use

When a thread exits due to an uncaught exception, the JVM reports this event to an application-provided UncaughtExceptionHandler.

If no handler exists, the default behaviour is to print the stack trace to System.err.

In long-running apps always use custom implementations of UncaughtExceptionHandler that at least log the exception.

Daemon threads do not prevent JVM from shutting down, other threads do.

Avoid finalizers.

PART III - Liveness, Performance, and Testing

Avoiding Liveness Hazards

Liveness - a concurrent application’s ability to execute in a timely manner.

Deadlock - thread A holds lock L and tries to acquire lock M, while thread B holds M and tries to acquire lock L.

A program will be free of lock-ordering deadlocks if all threads acquire the locks in a fixed global order.

Do no call an alien method with a lock held.

Invoking an alien method with lock held is asking for liveness trouble. The alien method might acquire other locks

(risking deadlock) or block for an unexpectedly long time, stalling other threads that need the lock you hold.

A program that doesn’t hold more than one lock at a time cannot experience lock-ordering deadlock. If you have to use more locks perform global analysis to ensure that lock ordering is consistent across entire application.

Use Lock.tryLock() to detect and recover from deadlock.

Thread dumps include locking info; which thread waiting for or holding which lock.

Livelock is a form of liveness failure, where a thread, while not blocked, still cannot make progress.

Performance and Scalability

Avoid premature optimization. First make it right, then make it fast - if it is not already fast enough.

Scalability - the ability to improve throughput when additional computing resources (memory, CPU) are added.

Measure, don’t guess.

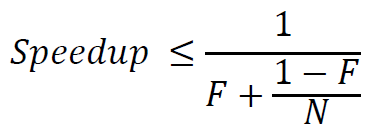

Amdahl’s law describes how much a program can theoretically be sped up by additional computing resources,

based on the proportion of parallelizable and serial components.

If F is the fraction of the calculation that must be executed serially, then Amdahl’s law says that on a machine

with N processors, we can achieve a speedup of at most:

Three ways to reduce lock contention:

- reduce the duration for which the lock is held

- reduce the frequency with which the locks are requested

- replace exclusive locks with coordination mechanisms that permit greater concurrency

Shrinking synchronized blocks can improve scalability, but the cost of synchronization is not zero. Breaking one synchronized block into

multiple synchronized blocks (correctness permitting) at some point becomes counterproductive.

It only makes sense to worry about the size of synchronized block when you can move substantial computation or blocking operations out of it.

Even though the below code is thread-safe, it is not very efficient, because all methods are guarded by this object.

@ThreadSafe

public class ServerStatus {

@GuardedBy("this") public final Set<String> users;

@GuardedBy("this") public final Set<String> queries;

...

public synchronized void addUser(String u) { users.add(u); }

public synchronized void addQuery(String q) { queries.add(q); }

public synchronized void removeUser(String u) {

users.remove(u);

}

public synchronized void removeQuery(String q) {

queries.remove(q);

}

}It can be refactored to use a lock splitting technique - instead of guarding both users and queries with the this lock, we can instead guard each with a separate lock. After splitting the lock, each new finer grained lock will see less locking traffic:

@ThreadSafe

public class BetterServerStatus {

@GuardedBy("users") public final Set<String> users;

@GuardedBy("queries") public final Set<String> queries;

...

public void addUser(String u) {

synchronized (users) {

users.add(u);

}

}

public void addQuery(String q) {

synchronized (queries) {

queries.add(q);

}

}

// remove methods similarly refactored to use split locks

} Lock splitting can sometimes be extended to partition locking on a variablesized set of independent objects, in which case it is called lock striping. For example, the implementation of ConcurrentHashMap uses an array of 16 locks, each of which guards 1/16 of the hash buckets; bucket N is guarded by lock N mod 16.

Alternatives to exclusive locks: concurrent collections, read-write locks, immutable objects and atomic variables.

When testing for scalability, the goal is usually to keep the processors fully utilized. Tools like vmstat and mpstat on

Unix systems or perfmon on Windows systems can tell you just how “hot” the processors are running.

If the CPUs are asymmetrically utilized (some CPUs are running hot but others are not) your first goal should be to find

increased parallelism in your program. Asymmetric utilization indicates that most of the computation is going on in a

small set of threads, and your application will not be able to take advantage of additional processors.

If thread is blocked by lock - thread dump indicates “waiting for monitor entry”.

Tests are not substitute for code reviews, and vice versa.

Explicit locks

synchronized locking has some limitations - threads waiting for intrinsic locks cannot be interrupted, so thread can be blocked forever.

Intrinsic locks also must be released in the same block of code in which they are acquired.

Unlike intrinsic locking, ReentrantLock

offers a choice of unconditional, polled, timed, and interruptible lock acquisition, and all lock and unlock operations are

explicit.

ReentrantLock provides the same mutual exclusion and memory visibility guarantees as synchronized keyword.

ReentrantLock should always be released in final block!

ReentrantLock is not a blanket substitute for synchronized; use it only when you need features that synchronized lacks.

ReadWriteLock - resource can be accessed by multiple readers or by single writer at a time, not both.

Object.wait [called on lock instance] atomically releases the lock and asks the OS to suspend the current thread, allowing other threads to acquire the lock and therefore modify the object state. Upon waking (after notify/notifyAll being called on lock instance), it reacquires the lock before returning.

Always test condition predicate before calling wait.

Always call wait in a loop.

Most synchronizers implement common base AbstractQueuedSynchronizer

The Java Memory Model

Initialization safety guarantees that for properly constructed objects, all threads will see the correct values of final fields that were set by a constructor.

Initialization safety makes visibility guarantees only for the values that are reachable through final fields as of

the time the constructor finishes.

For values reachable through non-final fields, or values that may change after construction, you must use synchronization to ensure visibility.

A data-race occurres when a variable reads and writes are not ordered by “happens-before”. A correctly synchronized program

is one with no data races, exhibits sequential consistency, meaning all actions happen in a fixed, global order.

Data race or race condition - when getting the right answer depends on lucky timing.

The most common type of race condition is “check-then-act”, where a potentially stale observation (check) is used to make

a decision on what to do next.

Never miss a post, subscribe to my newsletter

Never miss a post, subscribe to my newsletter